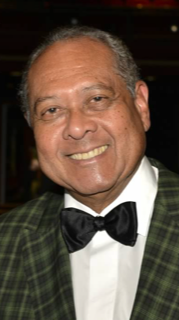

Little did Stefan Maxwell, BSc., MB, BS, FAAP, know his whole life was about to change when he made the decision to complete his pediatric residency in Miami, Florida, in 1978. He immediately created a bond with both Roger Medel, M.D., the future founder of MEDNAX and his Chief Resident at the time, and Greg Melnick, M.D., his Senior Fellow. When the two of them moved on to begin MEDNAX, Dr. Maxwell continued his residency while also moonlighting on the weekends with them at Memorial Hospital in Hollywood, Florida, the first hospital where MEDNAX had a presence.

At the end of his fellowship in 1983, Dr. Maxwell was asked by Dr. Medel to officially join their team at Memorial Hospital. Proving to be of great value to the team and filling in at multiple hospitals, Dr. Medel next asked him to move to a new opportunity in West Virginia, the first practice for MEDNAX outside of Florida. Dr. Maxwell laughs sharing how beautiful West Virginia was in the springtime, reminding him of his home country of Jamaica, but how terrifying it was come winter having to drive in the heavy snow—something he had never even seen before. Although the move was initially difficult, Dr. Maxwell fell in love with the hospital and has been there ever since.

He now has the privilege of coaching current medical students from the University of West Virginia. “I feel very strongly that people in training should be taught the right way to do things,” he states. “For instance, I asked somebody about how to diagnose a mass in a baby’s abdomen and the first thing they want to do is get a CT scan or an MRI.” He says teaching a more hands-on approach to students is very exciting and it’s often something they have not been introduced to before. He’s also able to learn from students since they have grown up in a very different time of medicine.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

In September of 2009, Dr. Maxwell began a study using the umbilical cords of newborn babies to determine the prevalence of substance use, specifically opioids, in pregnant women. There were leftover funds at the conclusion of this study, so Dr. Maxwell suggested using them to look into the use of alcohol in these mothers. Prior to this, there wasn’t a good marker for alcohol testing as urine tests were notoriously inaccurate. It wasn’t until the lab Dr. Maxwell and his team worked with introduced a blood test that had a three to four week “look back” period that they were able to study this more closely. The test involves looking at a specific compound that is incorporated in the membrane of red blood cells and changes when it becomes exposed to alcohol.

This kind of research is critically important as the global fetal alcohol syndrome rate is 0.6% of live births while the United States is a staggering 5.2% of live births. Dr. Maxwell and his team found an even higher percentage in their random sample of around 1,800 blood cards with the numbers falling in at 8.1%. He hopes that this test will eventually become incorporated into the standard newborn screens for every baby.

Long term alcohol exposure

He also stresses the importance of early diagnosis and monitoring of babies as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder often doesn’t present until intervention is too late. He says that babies exposed to high amounts of alcohol in the first trimester typically show physical abnormalities of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), but babies exposed in later trimesters aren’t always identifiable at birth. Their symptoms (which can escalate into more serious issues such as cognitive delays, slow physical growth, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), vision and/or hearing problems, poor memory, and many more) don’t present until around ages six to seven. Earlier diagnosis allows for tracking through the child’s life and may help explain these future issues.

In addition to getting this screen mandated, Dr. Maxwell says his next steps in this research are to increase funding for these kinds of projects. It’s currently unknown if exposure to opioids causes sustained damage in children, but we know alcohol does create irreversible damage in the brain. There needs to be more emphasis on this subject not for punitive measures, but to direct early intervention and education in the future.

Can't find time to read? Listen instead!